By Papa Shaw:

For the ordinary Sierra Leonean, electricity is not an abstract policy discussion. It is the difference between a small business surviving or collapsing, between students studying at night or giving up, between hospitals functioning or improvising in the dark.

It is therefore important to state, clearly and fairly, that recent governments have made visible efforts to improve energy supply. New generation projects, grid expansions, and international partnerships have increased capacity and reduced some of the worst shortages of the past. These efforts deserve acknowledgment. They reflect a genuine attempt to confront a longstanding national problem.

Yet appreciation should not silence scrutiny.

Because beneath the improving numbers lies a deeper question:

Are we solving Sierra Leone’s energy crisis or postponing it at the cost of deeper national debt and long-term dependence?

The Quiet Proposal That Raised a Loud Question.

In 2024, diplomatic discussions between Sierra Leone and the Russian Federation included potential cooperation in peaceful nuclear energy. Public statements confirmed that energy possibly even nuclear power was part of exploratory talks. No contract was signed. No feasibility study released. No parliamentary debate followed.

But the idea itself mattered.

For the first time in years, the conversation hinted at a permanent, generational solution not just more megawatts, but enduring energy sovereignty.

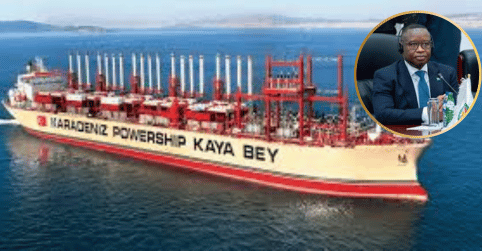

Shortly afterward, Sierra Leone announced substantial U.S.-backed financing for a gas-powered electricity plant. The project is concrete, funded, and progressing. It will add much-needed capacity. For this, the government again deserves credit.

But it also comes with a familiar price: loans that must be repaid, fuel dependency, and long-term fiscal obligations in a country already managing debt distress.

The contrast between these two paths one speculative but permanent, the other practical but debt-driven demands honest examination.

When Help Comes With a Clock

Gas plants work. No serious analyst denies this. But they do not last forever, and they do not free a nation from external dependence. Fuel must be imported. Maintenance often requires foreign expertise. Repayment schedules outlive political terms.

Nuclear energy, by contrast, is not an election-cycle solution. It is expensive, technically demanding, and politically risky. But when done properly, it provides stable, large-scale power for 40 to 60 years power capable of transforming industry, education, healthcare, and manufacturing.

Across Africa, nuclear energy is no longer theoretical. Other nations have pursued it with seriousness and long-term planning.

The question is not whether nuclear power is easy.

The question is why Sierra Leone repeatedly avoids what is difficult but lasting, in favor of what is quick but costly.

Geopolitics or a Failure of National Ambition?

Some observers dismiss the Russian nuclear discussions as diplomatic signaling ambitious talk without guaranteed delivery. That caution is valid. Investigative journalism demands skepticism.

But skepticism must apply equally.

Western-backed projects are not charity. They are structured financial instruments designed to protect investor interests as much as developmental goals. Development financing can coexist with genuine support, but it also creates leverage.

A nation permanently repaying energy loans is a nation with limited autonomy.

This is not a contest between East and West. It is a contest between short-term relief and long-term freedom.

Leadership, Loans, and the Politics of Survival

Another uncomfortable truth must be confronted carefully but clearly: borrowing is politically convenient.

Loans deliver quick announcements, groundbreaking ceremonies, and visible progress within a single political term. Long-term infrastructure especially nuclear or similarly permanent solutions demands continuity, transparency, and political maturity that extend beyond election cycles.

When leaders repeatedly choose debt-financed solutions over permanent ones, the burden does not disappear. It simply moves forward in time to the people.

Citizens pay through tariffs. Through taxes. Through stalled development.

Commending Progress, Demanding Vision

This investigation does not deny progress. It does not dismiss the government’s efforts to improve electricity supply. Those efforts matter, and they have eased real suffering.

But progress must not become an excuse to stop asking harder questions.

True leadership is not only about fixing today’s shortages. It is about ensuring that in 30 years, Sierra Leone is not still negotiating emergency power deals, still borrowing for generators, still rationing electricity while repaying yesterday’s loans.

A National Conversation We Can No Longer Avoid

Sierra Leone needs more than projects. It needs a national energy philosophy.

How much debt is acceptable in the name of development?

Which energy sources truly serve future generations?

Why are permanent solutions so often postponed?

Where is parliamentary oversight?

Where is public consultation?

Energy policy should not be negotiated quietly abroad and announced as a finished product at home.

Choosing Light That Lasts:

Electricity is power but power is also about choice.

The choice between temporary relief and lasting security.

Between political convenience and national responsibility.

Between endless borrowing and bold, future-focused investment.

Sierra Leone’s leaders have shown willingness to act. The next test is whether they are willing to think long-term, even when it is uncomfortable, complex, or politically risky.

The public, too, has a role: to demand transparency, to support serious debate, and to insist that development does not mortgage the future.

Because the darkest outcome is not power outages,

it is a nation that never stops paying for light it never truly owns.

![]() CCN Digital Media; Energy, Governance & Accountability

CCN Digital Media; Energy, Governance & Accountability